France’s Macron became a lame duck President this year. The Tory Party was dumped out of office at the UK general election in favour of a party of relatively inexperienced micro-focussed policymakers who have witnessed a remarkably short electoral honeymoon. Japanese PM Ishida was handed an electoral defeat even before he had officially taken office. In the US, the incumbent party has been swept aside. Also this month, Germany’s albeit coalition fell. In effect, most G10 governments have fallen. Two decades ago, I regularly spoke at a number of conference events in tandem with Lord Patten, the architect of John Major’s surprise 1992 UK election victory, and he was convinced that Opposition Parties never won elections, but existing governments sometimes lost them.

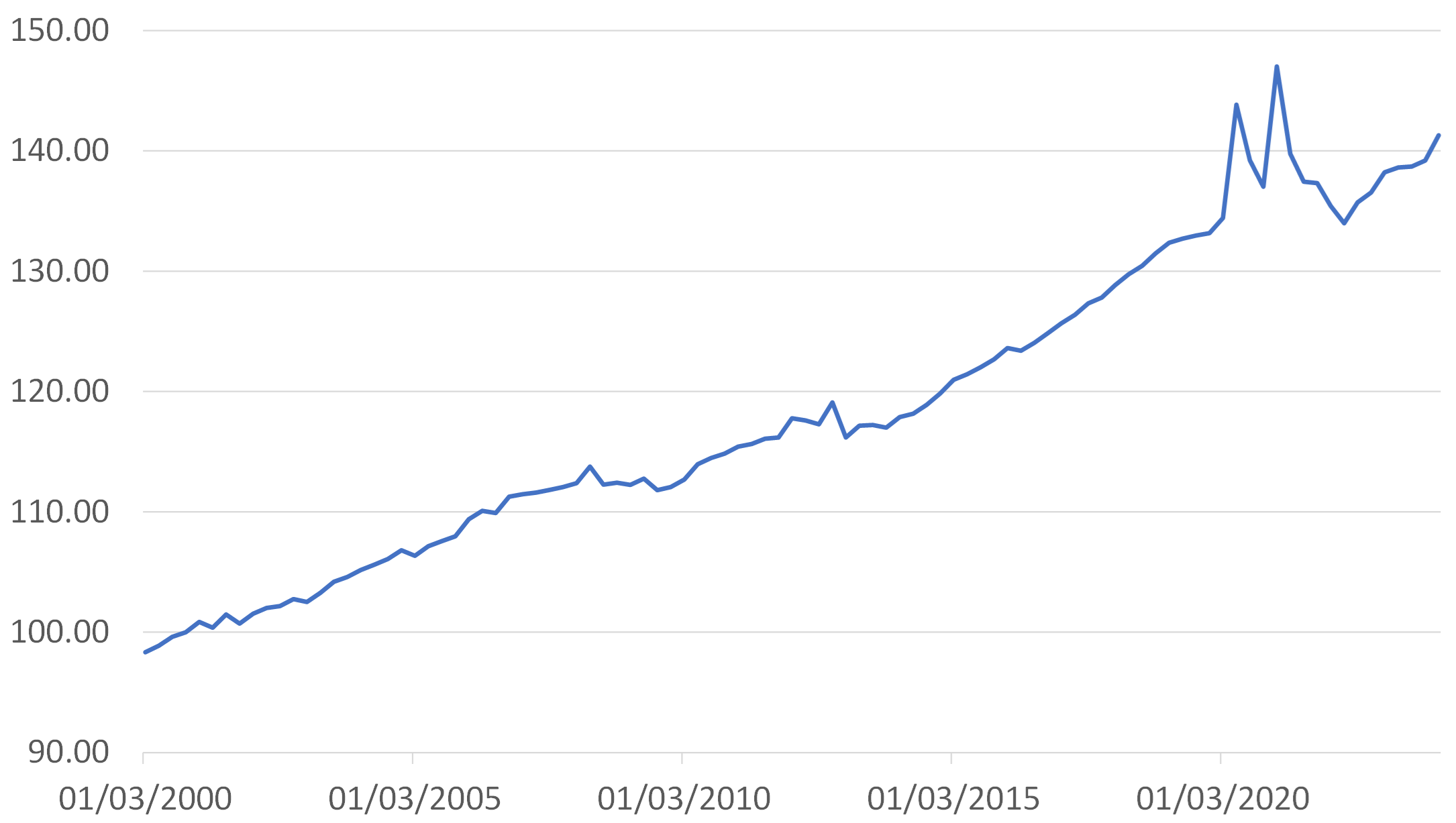

This year has clearly been the year of the Patten Maxim and this is hardly surprising, household real income growth has been modest over the last 15 plus years and non-existent over the last five (the chart below is illustrative rather than exact, but the message is clear). In reality, Japanese real incomes haven’t grown for a decade, German incomes have averaged less than half a percent per annum growth since the Euro was introduced, and although US growth has at least been positive, it has been notably sub-par by Postwar standards. As President Clinton one remarked, “it’s the economy, stupid”.

G3 Household Real Disposoable income

Index 2000 = 100

To remain in power, our latest batch of leaders will need to produce sustained household real income growth without compromising the sustainability of the planet, or they are going to have to produce a very compelling and accepted explanation for why they failed. This growth will not (cannot) come from endless further Demand Management, it will have to come from raising Supply Side Potential growth.

Usually, supply side reform requires mavericks or outsiders – just as a stock market index is by definition comprised of the “winners” from the previous period or regime, incumbent governments represent the status quo, which in many cases is one that is credit dependent, monopolistic, highly regulated, and possesses a tendency to obfuscate any inconvenient narratives or facts behind smokescreens of vox-pop-friendly policies.

Existing governments – and index managers – don’t normally vote for regime change and therefore it takes outsiders such as B-Movie actors from Hollywood or village shopkeeper’s daughters from rural England to enact change. The men in grey suits usually abhor change, not least of all because it disrupts their natural order of things…

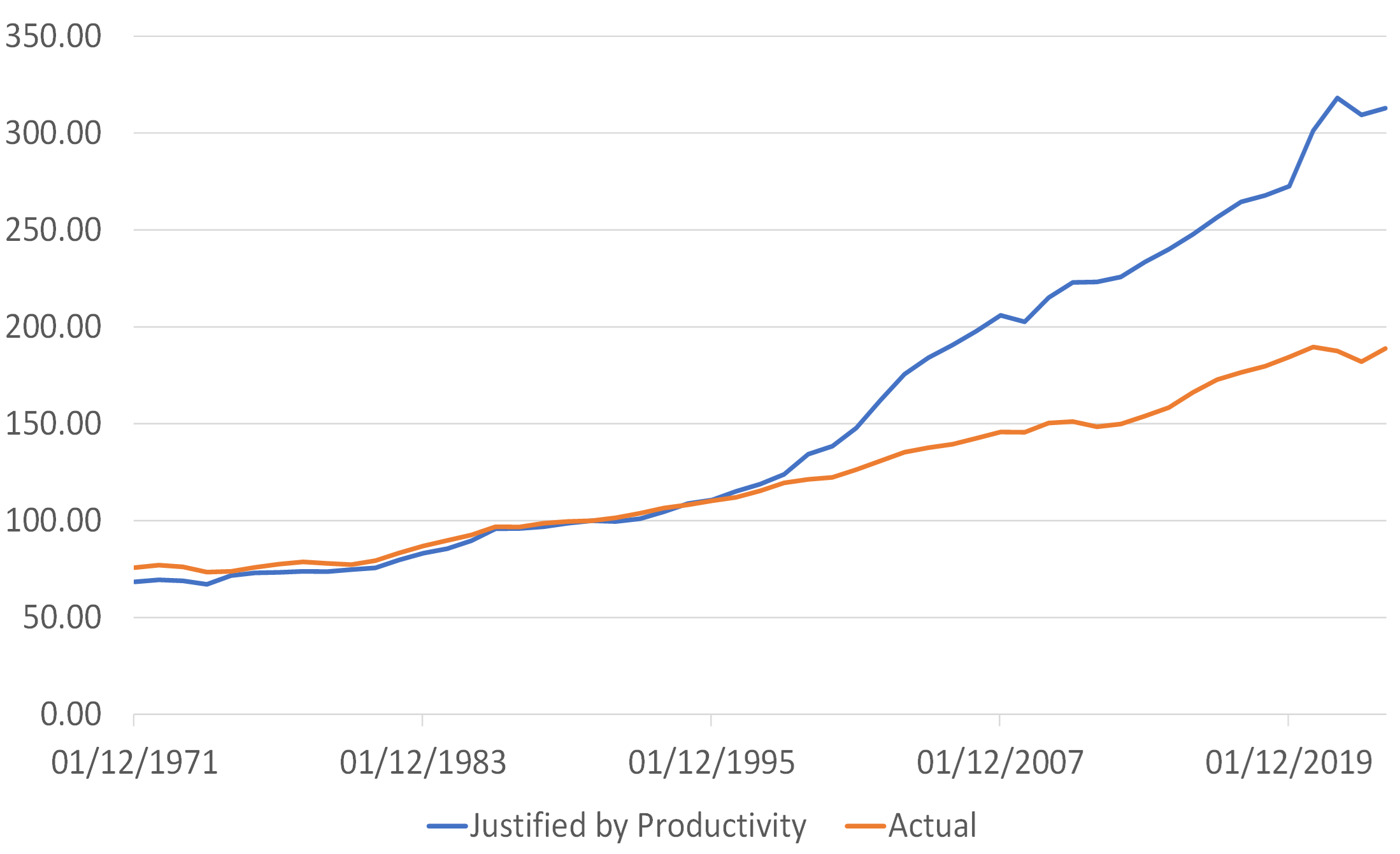

Will President Trump be an agent of change? I recently re-read Trump-advisor Scott Bessant’s piece justifying tariffs on certain countries and it is possible to broadly agreed with his comments. For twenty years we have suggested that the bringing of a (managed) output maximizing large economy like China into a profit-maximizing world trading system was sub-optimal, and we certainly blame the recent over-appreciation of internal (sometimes known as Ricardian) real exchange rates in the West on this mistake.

Over time, it is true that the prices of non-traded goods should rise relative to trade goods according to the productivity differential between the two sectors, but North Asia’s deflation-inducing output maximizing behaviour in the goods markets, and the West’s low interest rate / credit-boom-fostering response to falling goods prices has created a record overvaluation of Western Real Exchange Rates.

USA: Real Exchange Rate

1970 = 100

Not since Japan in the late 1980s, or the USA in the late 1920s have we witnessed a similar degree of internal real exchange rate overvaluation. In this environment, it is of no wonder that economies have struggled to produce real sustainable growth and have become so reliant on either private or public sector credit flows for what growth they have witnessed…

Moreover, this overvaluation problem has contributed to income inequality and low productivity growth (by encouraging resources into low productivity growth sectors such as property) that has led to the government-popularity-sapping weak trend in household real incomes. This is the problem that policymakers must now solve.

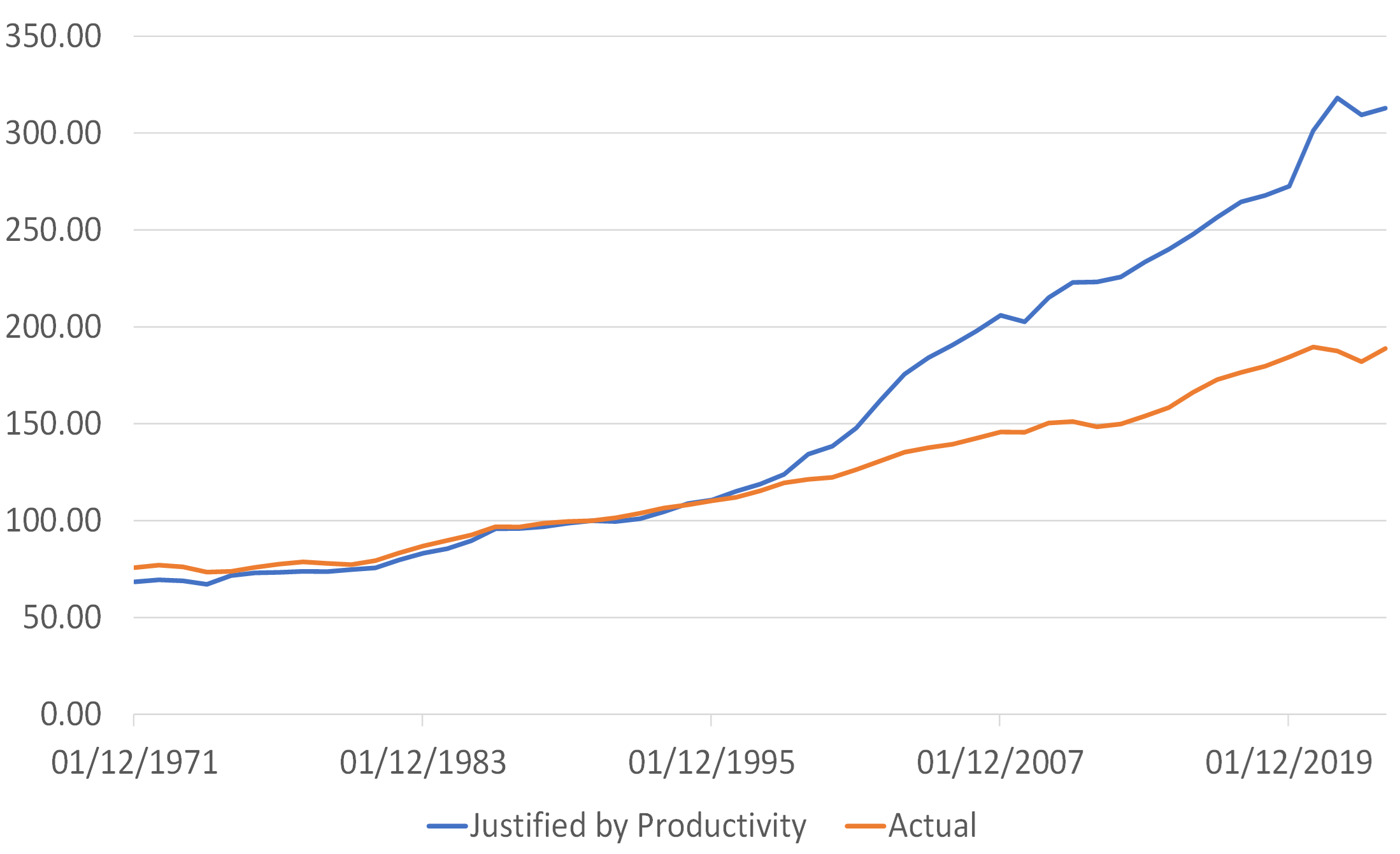

If we want to see a return to sustained efficient growth in the West over the long term, and political stability, we need deregulation, anti-monopoly measures, and most of all a depreciation in the internal real exchange rate. Or, to express this another way, we need to see non-traded goods prices fall relative to the prices of traded goods. In practice non-traded goods prices are heavily influenced by property prices, since the suppliers of non-traded goods by definition have to be based – and of course live – in the locale. Notionally, a 10 - 20% tariff on imports that raised traded goods prices would seem a quick fix, and it would also have theoretical support given the planned economy vs. free market economy problem within the WTO.

USA: Traded & Non Traded Goods Prices

Index 1985 = 100

The problem is, of course, that rising traded goods prices will tend to deflate real incomes globally, either by damaging the incomes of exporters within the US’s external suppliers, or by raising the prices faced by US consumers in the shops. Granted, the domestic real income deflation in the US could be offset by tax cuts (which would need to be carefully targeted at those needing “compensation”), but as we have seen the threat of rising prices and potentially rising budget deficits tends to raise bond yields / lower bond prices. Higher yields are something that can reduce both the demand for, and potential supply of, credit to all sectors of the economy, including those most in need of further injections of credit in order to sustain their business models.

Given the debt overhang in the property markets, and the cash flow negative position of many of the US’s non-traded goods suppliers, rising yields tend to be deflationary for domestic prices – we might therefore see both a tariff-induced rise in traded goods prices and a high yield-induced decline in Non-traded goods prices.

Of course, this would “solve” the real exchange rate problem but the deflation of non-traded goods prices would adversely impact the economy’s financial health, possibly quite significantly. Japan chose this route (deliberately) during the 1990s as a matter of social policy (high asset prices and wealth inequality were deemed un-Japanese by Governor Mieno) and of course the results were painful (although they were exaggerated by the structural rigidities present in the economy). Fed Governor Strong’s personal prejudices in 1929 may have had something to do with the choice to opt for Non-traded goods price deflation in the USA following the Roaring 1920s Credit Boom / Original Goldilocks economy (the 1920s version of the Goldilocks economy relied on European export price deflation to offset higher US internal inflation – history does rhyme if not repeat…).

Here we have the central challenge or contradiction facing Trumpnomics. Can the necessary internal real exchange rate adjustment (which is implicit in Mr Bessant’s article and which we assume will be the centre piece of the new President’s strategy) be achieved without crashing household real incomes? We suspect that the answer is no, even if the exact routing is yet to be decided.

As we noted above, higher traded goods inflation would undermine real incomes in the majority of the economy, while potentially also crashing the bond markets and by implication the credit system. This would likely have deflationary consequences for much of the non-traded economy and of course employment trends. The casualties within the financial sector would not be insignificant under this scenario, and most of the household sector (outside some protected goods manufacturers) would certainly be worse off.

This scenario would represent something of an evil Goldilocks – rising traded goods prices and falling non-traded goods prices. The impact of evil Goldilocks on markets would probably be just as negative as Good Goldilocks was positive for markets during the 2000s.

However, given Mr Trump’s own background and that of his corporate sponsors, we suspect that crashing the non-traded goods sectors and creating a credit crunch is probably not high on his agenda, so we suspect that his Presidency will indeed ultimately tend to be an inflationary one over the long term.

Tariffs do seem probable (= inflation from higher import costs plus the higher costs of onshoring) but we suspect that, despite Mr Powell’s rather emphatic “No!” at the recent FOMC Q&A, the Administration will ultimately seek to find some way to ensure that are sufficiently low short term rates to hold long end yields down even as inflation rates miss-behave (this was achieved in 1993 and of course the mid-1970s - perhaps a Trump-influenced Fed could even look to some form of implicit YCC). In short, we expect Trump II to ultimately produce a mix of higher inflation and bond market-centred financial repression as we move into 2026.

With these trends in mind, over the next 6 months we foresee rising real yields a as markets increasingly come to fear inflation & deficits, but ultimately as dollar yields move towards the pain threshold of 5.0% on UST10Y, we could see the (non-traded goods) economy crumble and a deflation scare ensue, which in turn forces a Fed-induced collapse in the yield curve and ultimately a “swerve” to sustained inflation from 2026 onwards.

Looking further ahead to 2028/9, we can easily imagine that years of inflation / financial repression will have led to another lost five years for household real incomes. At this point, Washington will simply need a credible economic-reform minded “outsider” to walk into the White House on an inflation-busting mandate…

Disclaimer: These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed by Nikko Asset Management New Zealand Limited (Company No. 606057, FSP No. FSP22562), the investment manager of the Nikko AM NZ Investment Scheme, the Nikko AM NZ Wholesale Investment Scheme and the Nikko AM KiwiSaver Scheme. This material has been prepared without taking into account a potential investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs and is not intended to constitute financial advice and must not be relied on as such. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance. While we believe the information contained in this presentation is correct at the date of presentation, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given, and no responsibility is accepted for errors or omissions including where provided by a third party. This is not intended to be an offer for full details on the fund, please refer to our Product Disclosure Statement on nikkoam.co.nz.