Despite its small size and geographic location, New Zealand has led the World in a number of fields – physics, Postwar economic theory (Bill Phillips was born in NZ), inflation targeting (amongst the first to make this a statutory target), globalization, and of course in many sports. It is therefore of concern that the NZ economy has fallen into a deep recession that has witnessed real GDP per capita fall back to where it was just before the Pandemic struck. We must wonder whether NZ is once again leading the World, albeit in a race that it probably does not want to win or even compete in.

In general, Western democracies tend to be profit-maximizing economies that allocate resources according to the (relative) price system. There are shortcomings to this model, particularly around the provision of public goods, and they can be prone to distortions (particularly when price signals become distorted, perhaps by interest rates being too low, by monopolies, or when companies prioritize short term cash flow over business sustainability) but, like democracy itself, the system more-or-less works.

At the other end of the spectrum lie the planned economies, which by definition allocate resources according to some central strategy. In general, these tend not to be democratic systems. Lying in between are the (usually) single party / fledgling democracies of Northeast Asia that seek to maximize employment and output, rather than profits and cash flow. The maximization of output is often for reasons of “national security”, while maximizing employment is usually to provide a degree of legitimacy to, or at least acceptance of, the limited political system. This type of system has usually been excellent at providing periods of rapid industrialization but it often struggles in the transition to amore service sector orientated domestically-driven economy. Indeed, most of these output maximizing economies tend to be overly reliant on their export sectors to absorb the high levels of production.

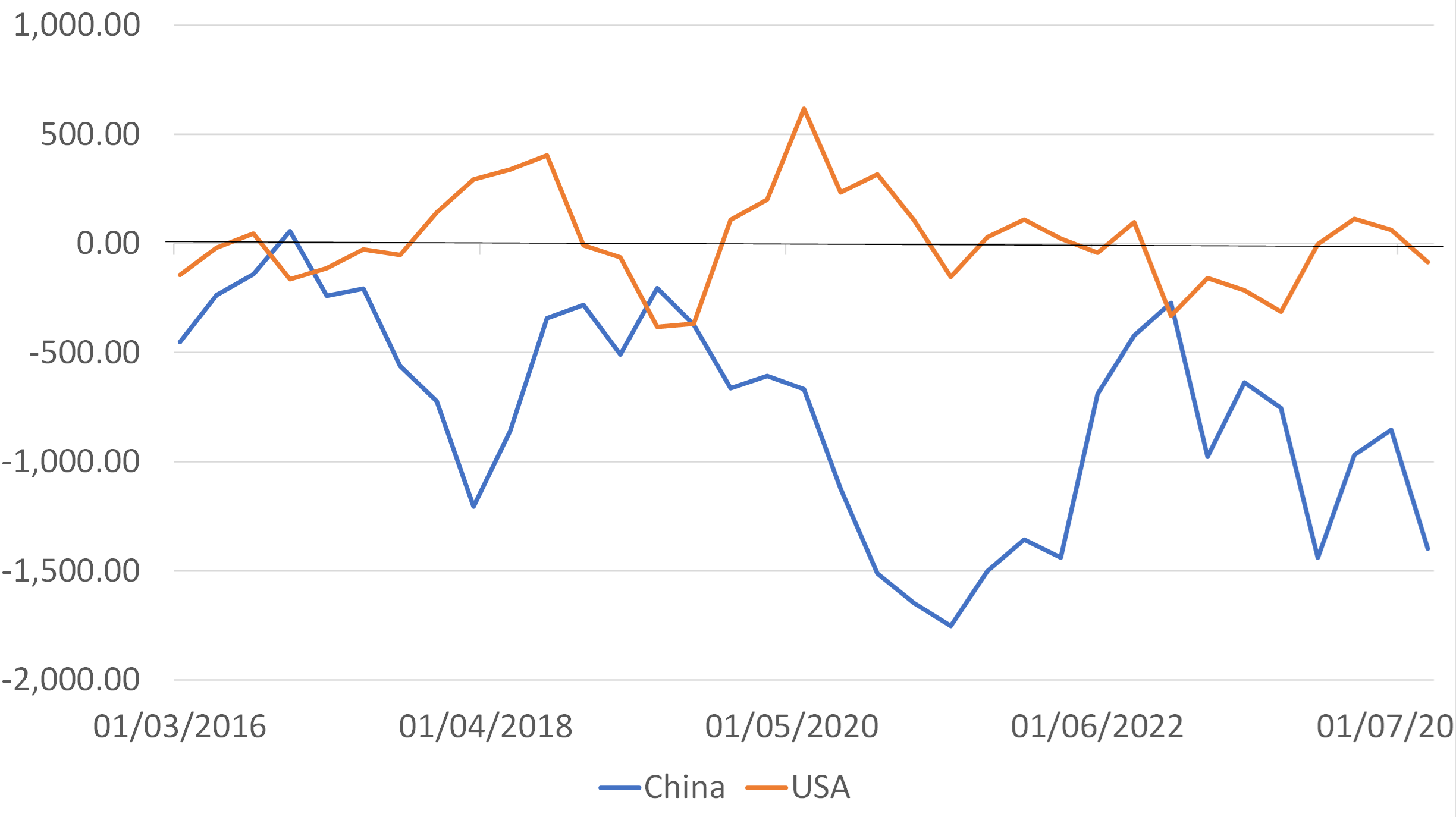

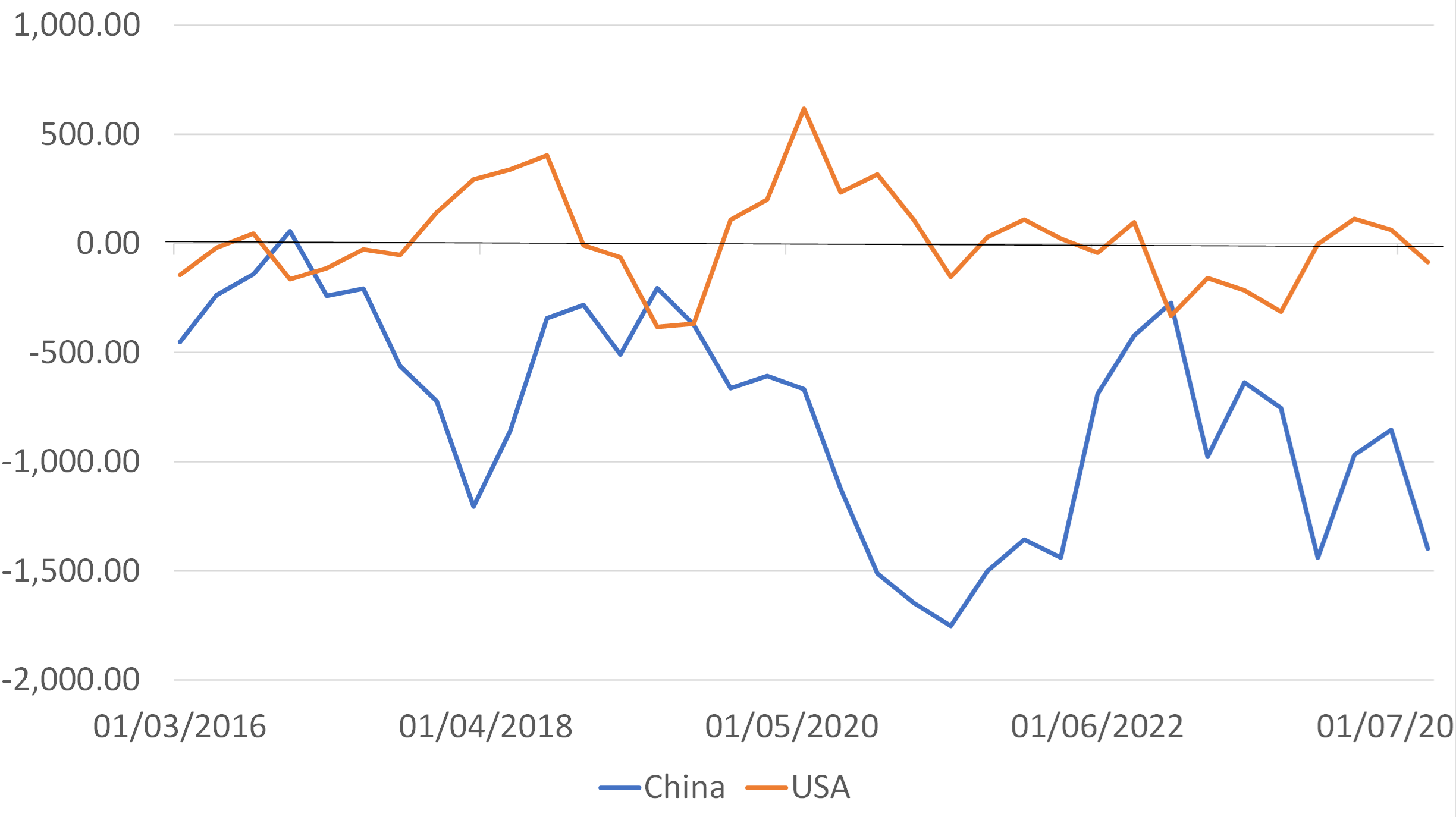

One key difference between the North Asian and Western systems is the financial behaviour of corporations. Western corporations tend to run with small cash flow deficits or occasional surpluses, while the Nort Asian economies have typically run with large financial deficits as they have prioritized producing “things” over producing “cash”.

Corporate Sector Financial Balance PRC vs. USA

USD billion over 4Q

USD billion over 4Q

Ultimately, both systems have their pro’s and con’s; both are valid economic models but what they cannot do is optimally co-exist within the same open trading system. When the two systems were rammed together under the auspices of the WTO and the rush for globalization during the mid-1990s, they unleashed forces that have taken the World to where to the fragile position that it occupies today: devoid of productivity growth and overly reliant on credit.

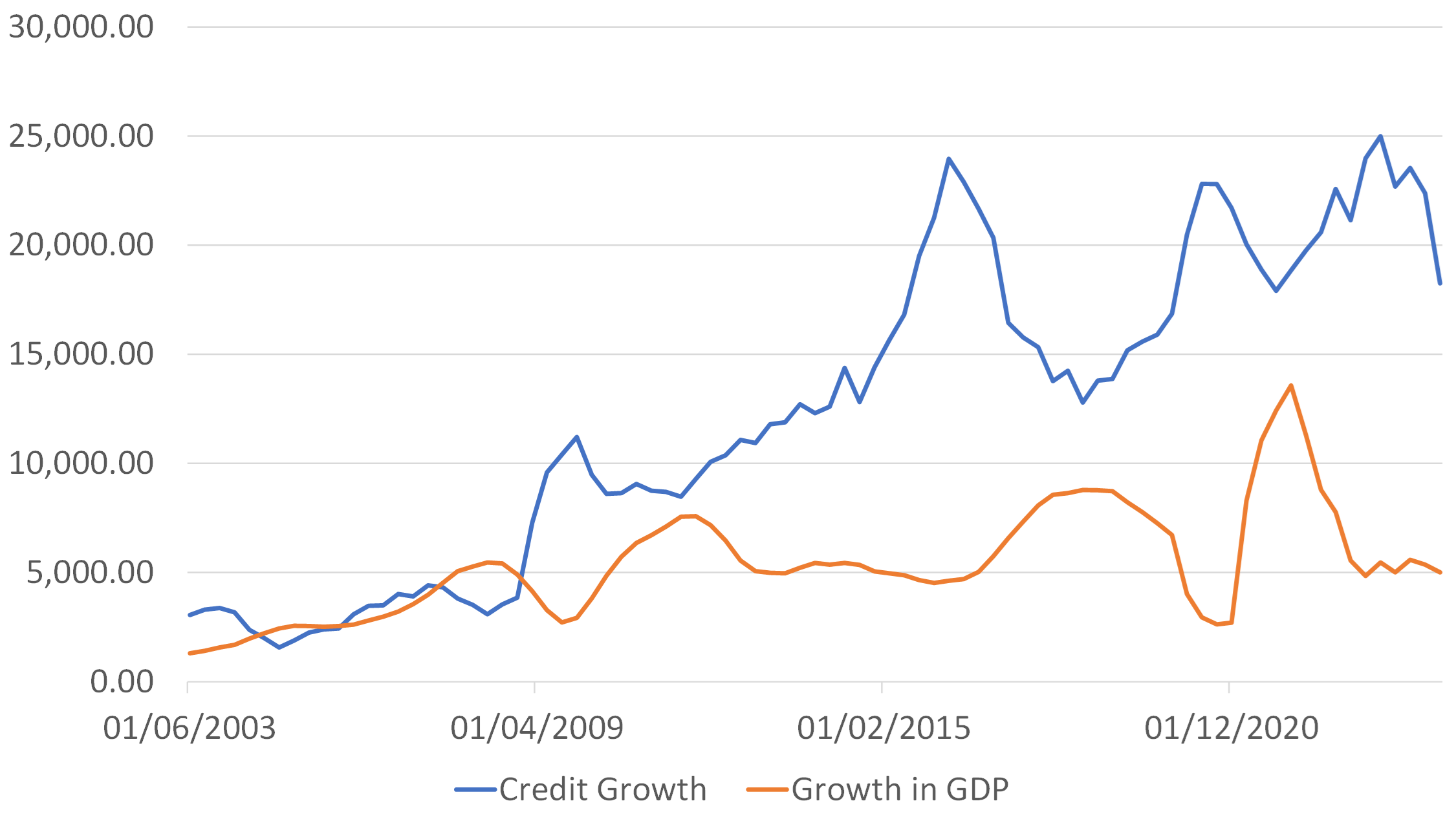

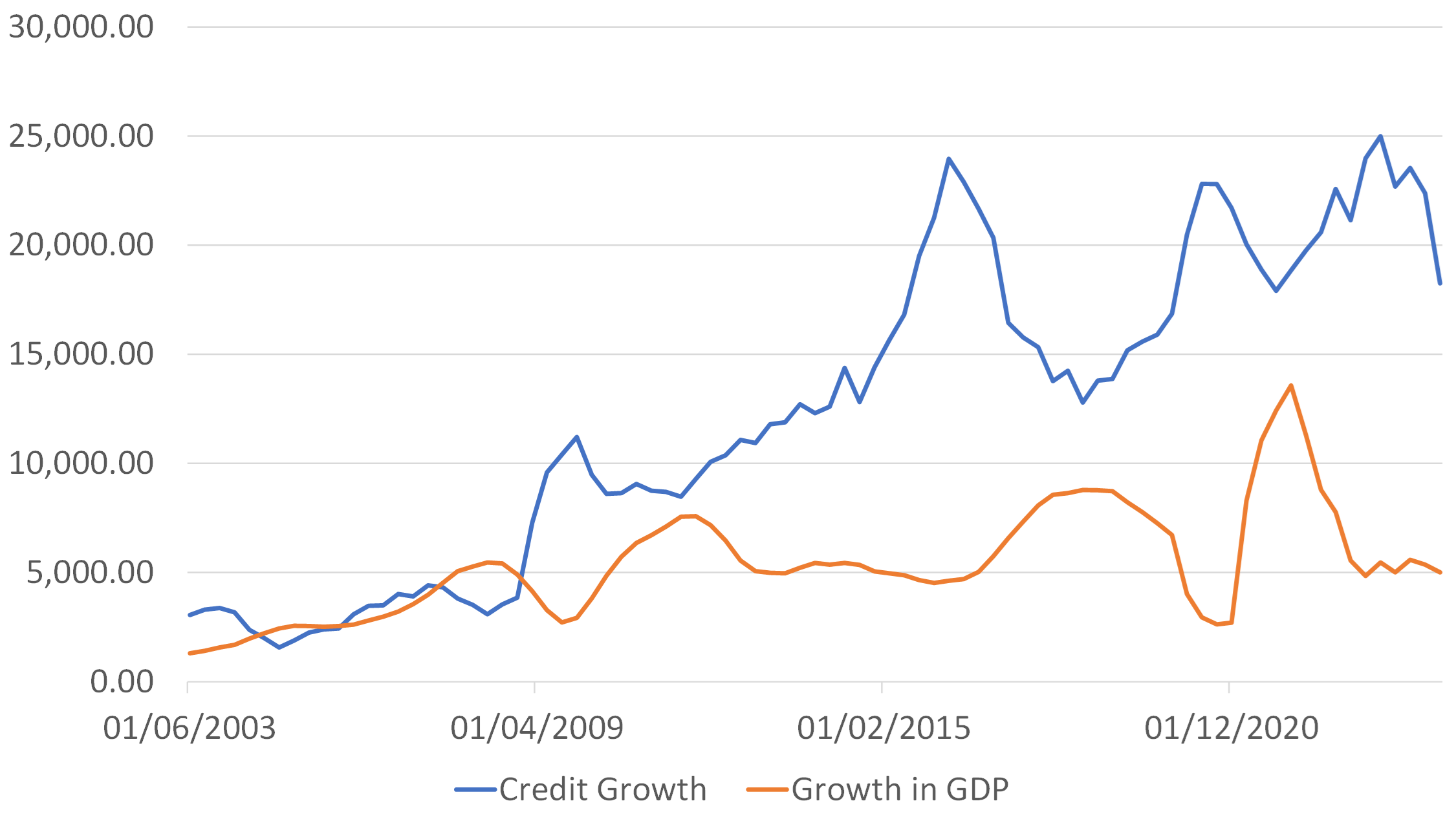

North Asia’s reliance on credit has been visible for decades. Japan’s Postwar reconstruction was reliant on cheap lending to companies so that they could fund the large financial deficits that were naturally the result by the rush for heavy levels of capital spending and aggressive pursuit of market share. The other Asian economies – including more recently the PRC - naturally followed suit. Indeed, we have noted that whereas Japan’s companies typically borrowed 3 – 5% of GDP per annum during the 1950s and 1960s, and took 20 years to build its industrial complex, Korea borrowed twice as much and “halved” the development time during the 1980s. China was even more aggressive in this regard during the 1990s. Of course, all this borrowing led to exponentially rising debt to GDP ratios, at least until some form of financial calamity befell the lenders – Japan’s banking crisis during the early 1990s or the Asian Financial Crisis in the late 1990s being two obvious examples.

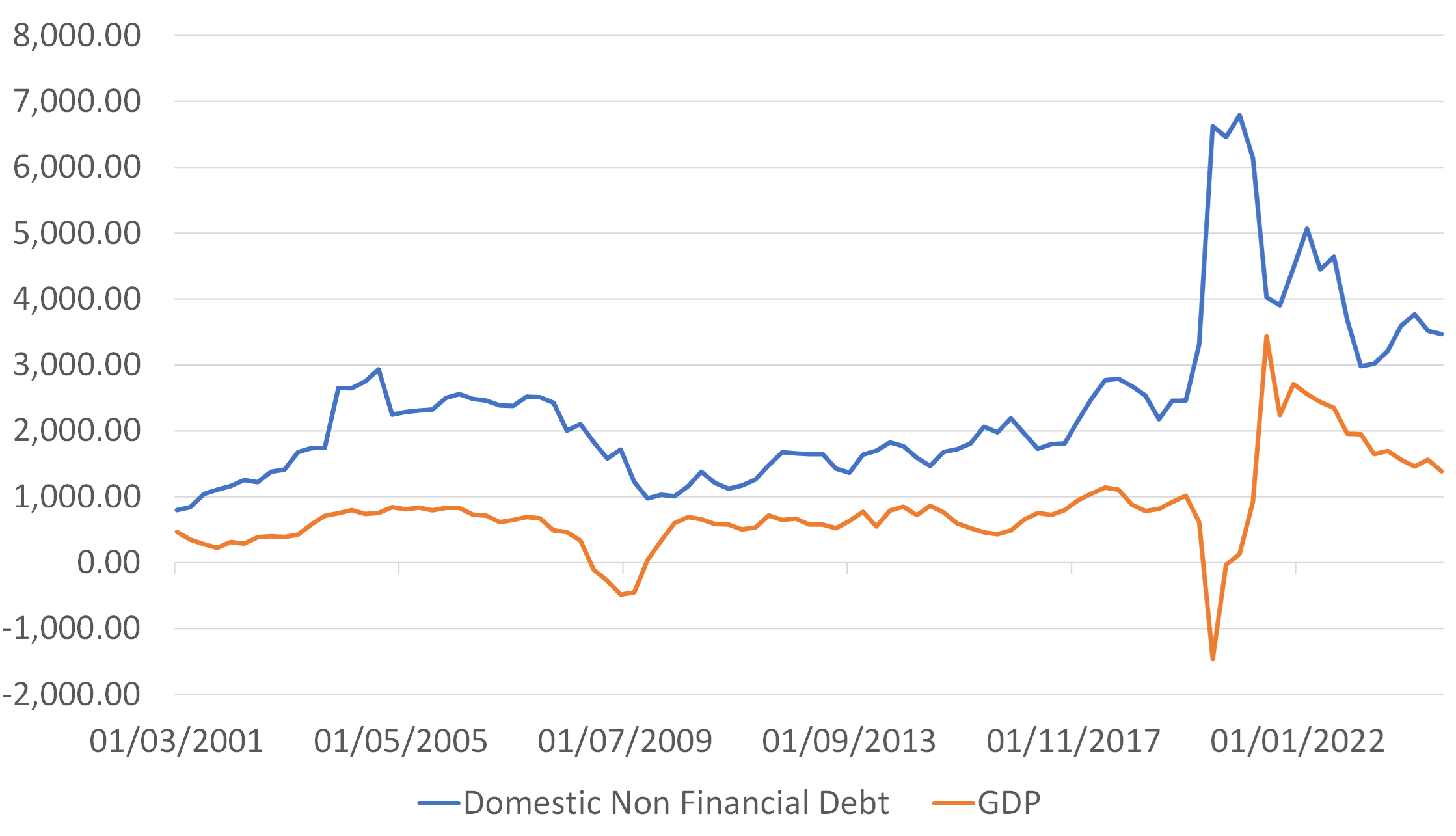

China: Nominal GDP and Credit Trends

CNY billion change over 4 Quarters

CNY billion change over 4 Quarters

The West’s addiction to credit was more subtle. The period of intense globalization of supply coincided with many central banks following the RBNZ’s lead into inflation targeting regimes. As low-priced goods (the production of which did not generate what economists call a normal profit) arrived from the Asian output-maximizing economies, they naturally caused inflation rates in the West to drop. Traded goods prices typically account for between a quarter and a half of a CPI, and so the deflation in these sectors caused the headline inflation rates to fall below target.

Faced with this “problem”, Western central bankers cut rates and liberalized the supply of credit so that they could cause faster inflation in their non-traded goods sectors to offset the deflation in the traded goods sectors. Soon, it was costing more to go out for dinner than to buy a TV set and stay at home…

With relative prices rising in the non-traded goods sectors in the price-mechanism-driven Western economies, this soon caused a flow of resources out of the productivity=growth-generating and relatively equitable manufacturing sectors and into the generally low productivity growth / high income inequality service sectors. Moreover, land and property are the ultimate non-traded goods and certainly they are the principal cost of doing business / cost of living in non-traded goods sectors. House prices soared, affordability declined, and wealth inequality deteriorated.

Crucially, the inflation of property prices generally required heavy levels of borrowing, while the lack of productivity growth in the service sectors subdued median real wages and left consumers reliant either on themselves borrowing more in order to sustain their consumption, or on governments borrowing on their behalf in order to top up private sector incomes.

In Asia, companies required massive injections of credit to sustain output; in the West households and governments became addicted to credit to sustain their spending.

While credit could flow in both systems, this strange disequilibrium appeared oddly sustainable. The political environment was of course deteriorating but in the 2010s and “protest votes” by electorates were generally dismissed as “one-offs” or the result of electorate stupidity. However, the Pandemic and the response to the Pandemic finally revealed the flaws in the system.

Western governments used too much credit and created too much money, with inflationary consequences that have required higher rates and some (modest) degree of credit stringency. Many Western governments performed poorly during the Pandemic, and thereby emboldened their electorates to become more questioning and demanding. Meanwhile, the Pandemic disrupted Asia’s supply lines and the demise of China’s banking system (itself in part the result of the worsening geopolitics) took the PRC to the point that Japan had reached in the early 1990s. China today, like Japan then, needs a new model but its political system is struggling to deliver the required changes.

Without further inflows of credit, China’s system is struggling and growth has evaporated. In much of the West – with the notable exception of the USA – we still have weak income growth but we no longer have the credit “top up” to spending power. Nowhere is this more evident than in New Zealand – productivity growth and therefore real income growth has been minimal or non-existent for decades and the RBNZ’s more hawkish stance has removed the credit prop to growth, with obvious consequences.

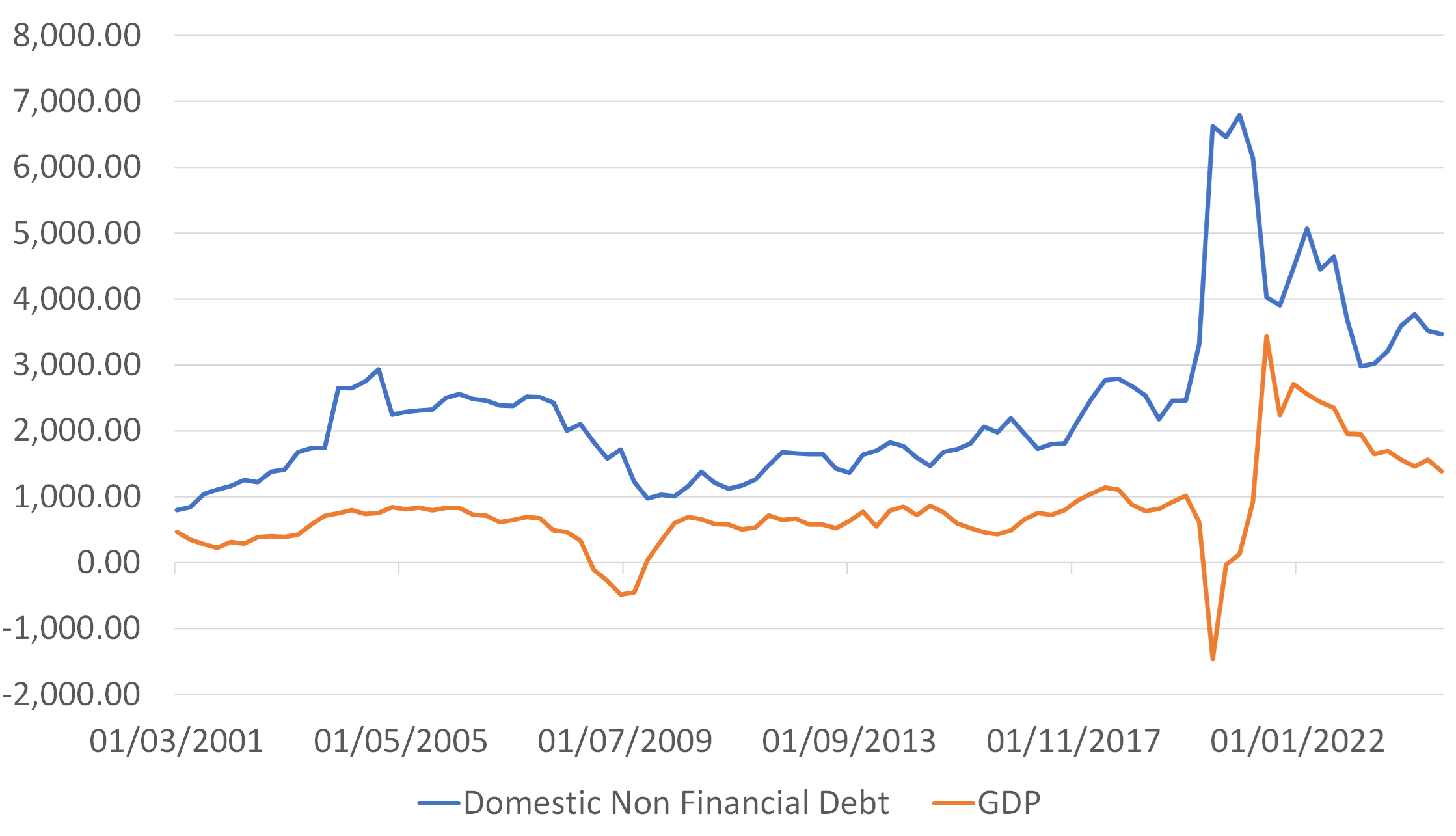

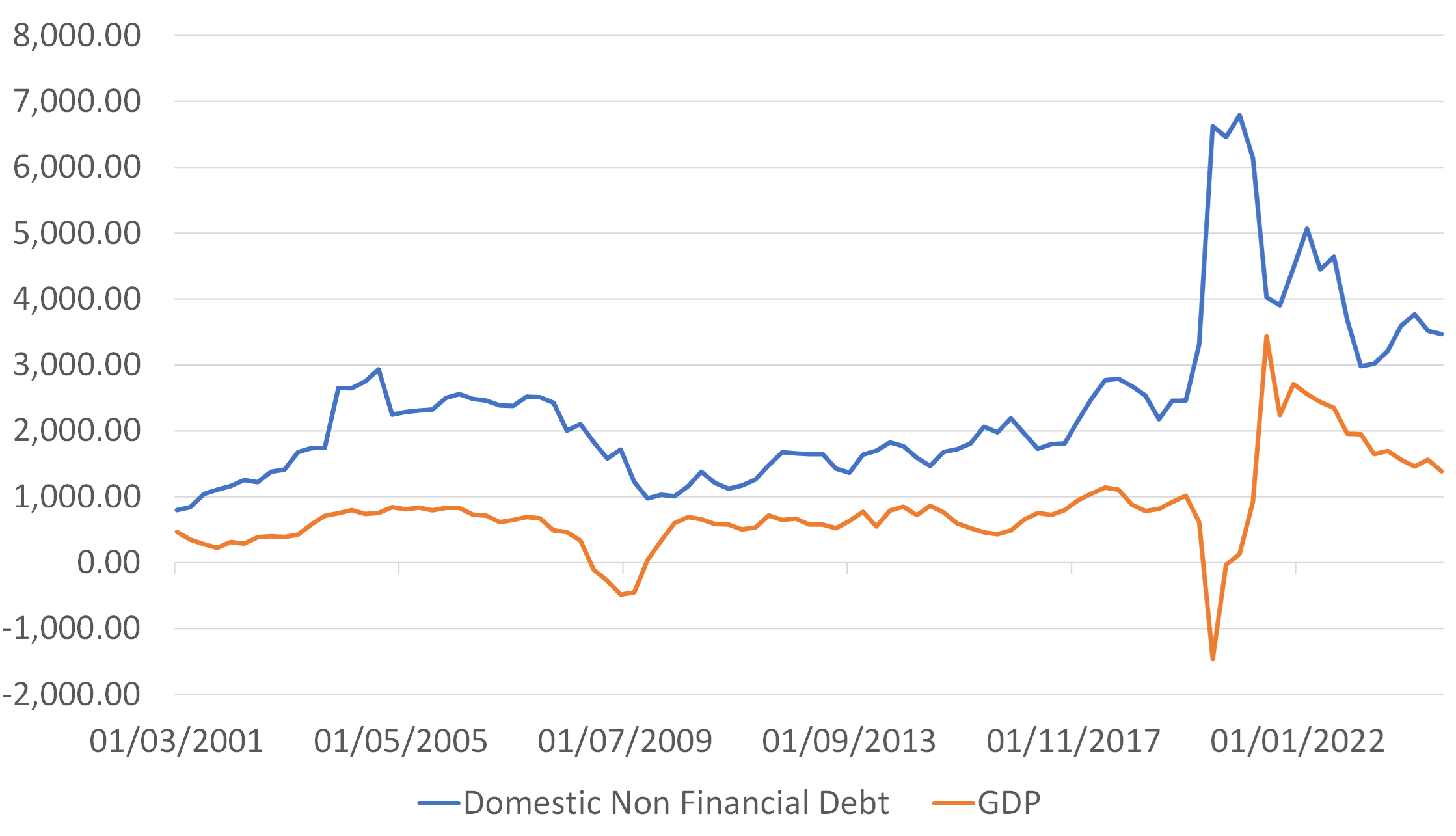

The US appears different. It is true that it has a little more productivity and income growth than many of its peers but what truly sets it apart is that it still has credit – the Federal Government is still borrowing very aggressively and the new private market channels are providing a new form of almost invisible but still ample credit to companies and, implicitly, their proprietors. The US is different not because it has escaped the shortcomings of the Post Globalization World but merely because it is taking the old credit-financed model – or anaesthetic – to new highs. The rate of debt growth in the US relative to GDP is starting to look a lot like it did during the NASDAQ Bubble and just prior to the GFC.

USA: Domestic Non Financial Debt Growth

And GDP growth, USD billion over rolling 4Q

And GDP growth, USD billion over rolling 4Q

During my career, the US has experienced no less than four major credit cycles. The mid-1980s was centred around the bank- and corporate-bond financed LBO boom, and a property boom financed by the Savings and Loans / Thrift institutions. The late 1990s NASDAQ bubble was predominantly financed via the corporate bond markets and investment banks. The Mid 2000s boom was of course centred in the mortgage markets and all the derivatives that had sprung up around these instruments. On each occasion, policymakers were slow to react because they didn’t keep up with the innovation that was occurring and therefore found it hard to see the cycle for what it was, i.e. “just another credit boom”.

Crucially, each cycle had its Achilles Heel. The LBO boom struggled when yields rose relative to income growth, as of course did the S&L boom. The NASDAQ Bubble burst when the flow of corporate credit was interrupted by higher rates and a clampdown by the Fed on some of the more esoteric flows into the markets during mid 2000. The mortgage boom failed when the matrix algebra employed within the derivatives markets failed. What could take down the latest iteration of credit boom?

We have a one-word answer to this: bonds. Higher yields would of course be a problem for the borrowers – both in the private and public sectors. More subtly, the flows of credit in this version of a leverage boom pass through (often on numerous occasions) the collateralized lending markets. In general, bonds are the collateral but a sharp decline in bond prices will reduce the pool of available collateral and thereby cause a decline in the stock of credit available. This could have as dramatic an effect as the Fed’s withdrawal of funding flows for the NASDAQ bubble in 2000s or the compliance-department-led collapse in the Mortgage Derivatives markets in 2007.

High bond yields would also pose a direct threat to the US equity markets. Since 9-11, with only a brief interlude during 2006-8, the cash yield on equities in the US has usually exceeded that of the US Treasury market if one makes allowance for the stock buybacks and Employee Stock Option payouts. However, this situation is changing, the yield on the equity markets has started to fall away and bond yields have started to rise – equities no longer yield more than bonds and the last time this happened…

USA: Cash Yield on Equities vs UST10 Y>

(includes ESO and Buybacks)

If the equity market were to suffer, they so too would the private market channels and hence the US’s ability to sustain its latest iteration of a credit boom. If this boom were to falter, then one only has to look at New Zealand’s recent performance to see just what will happen next.

In the near term, sticky inflation and the prospects of heavy levels of government borrowing may well continue to stress the bond markets but, as bond prices decline and yields rise, we fear that the fragilities inherent within this latest iteration of a (US) credit boom will be laid bare and that a recession could then unfold remarkably quickly. Of course, there would then be a policy response to that, but the discussion of what form that might take will have to wait for another report…

Disclaimer: These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed by Nikko Asset Management New Zealand Limited (Company No. 606057, FSP No. FSP22562), the investment manager of the Nikko AM NZ Investment Scheme, the Nikko AM NZ Wholesale Investment Scheme and the Nikko AM KiwiSaver Scheme. This material has been prepared without taking into account a potential investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs and is not intended to constitute financial advice and must not be relied on as such. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance. While we believe the information contained in this presentation is correct at the date of presentation, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given, and no responsibility is accepted for errors or omissions including where provided by a third party. This is not intended to be an offer for full details on the fund, please refer to our Product Disclosure Statement on nikkoam.co.nz.