A few weeks ago, we began experimenting with the hypothesis that households – and even some governments – were starting to reassess their long-term income expectations. Years of weak productivity growth, concerns over economic efficiency, the cost of living, the climate and troublesome geopolitics are all likely weighing on confidence in the future, along with the seemingly changed outlook for interest rates. My recent travels have hardened our view and increased our conviction in the notion that there has been a structural change in many household’s “permanent income expectations” with the result that they are now much less inclined to borrow income from the future in order to sustain consumption today.

This change in attitudes is not occurring uniformly across the globe. For a variety of reasons (including its economic reliance on China & tourism, and a miss-step by the RBNZ leadership), New Zealand is clearly at the vanguard of this shift, with the result tht the domestic economy is already experiencing a crunching recession that is threatening to turn deflationary. Australia is also beginning to witness a change, its exports to the PRC had proven strangely resilient until a few months ago but they have recently succumbed and the economy looks to be wilting. Elsewhere, we understand that the “German middle ground” is becoming increasingly pessimistic. Japan’s supply side is showing some signs of a renaissance but consumers nevertheless remain cautious – inflation will cost them dearly if it is sustained.

In the UK, the election process has made the situation a little more complex – there was a period of monetized deficits that boosted the economy - but we suspect that as the new government’s honeymoon period fades (probably very quickly), attitudes will change. If nothing else, the new government seems to be paring back some of its promises as it is obliged to confront the economy’s reality. So far, households in the US seem not to be capitulating, although the weakness in the savings rate data perhaps suggests that an increasing number of households are finding conditions tougher, despite the spendthrift government.

We also suspect that much of Asia is on the cusp of a major reassessment of the future. We find it of immense significance that the recent bout of US inventory restocking (ahead of expected tariff increases) has not been reflected in stronger region-wide export trends. Over the last thirty or so years, we have witnessed rising US orders give rise to export cycles in Asia but on this occasion the increase in demand from the US has not been sufficient to overwhelm the drag emanating from China’s economy. There has been a stimulus to the region from the US, but it has been lost in the implications of the weaker China situation.

We are of course aware that many are becoming more bullish on the outlook for China’s growth following a few policy statements vis-à-vis the property markets. However, the hard data shows the run on the banks continuing, hence the recent announcement of “austerity” in the sector. Despite this troubling situation, the public sector counterparts to liquidity (i.e. PBoC lending to banks and the banking system’s operations within the bond markets) look to be veering towards what might be described as Quantitative Tightening. In fact, China, despite its weak economy, looks to be doing more effective QT than many of the Western governments that outwardly claim to be conducting QT…..). Unsurprisingly, credit trends are continuing to soften, something that will be immensely painful for the cash flow negative corporate sector.

To us, China looks to be entering a classic Keynesian Paradox of Thrift in which the private sector is either trying to – or being obliged to – save more with the result that incomes are deflating and the actual amount of realized saving is declining despite the higher savings rates. Unless this tendency is countered via a significant fiscal easing (and at present there are no signs of the latter), the economy’s path risks accelerating to the downside.

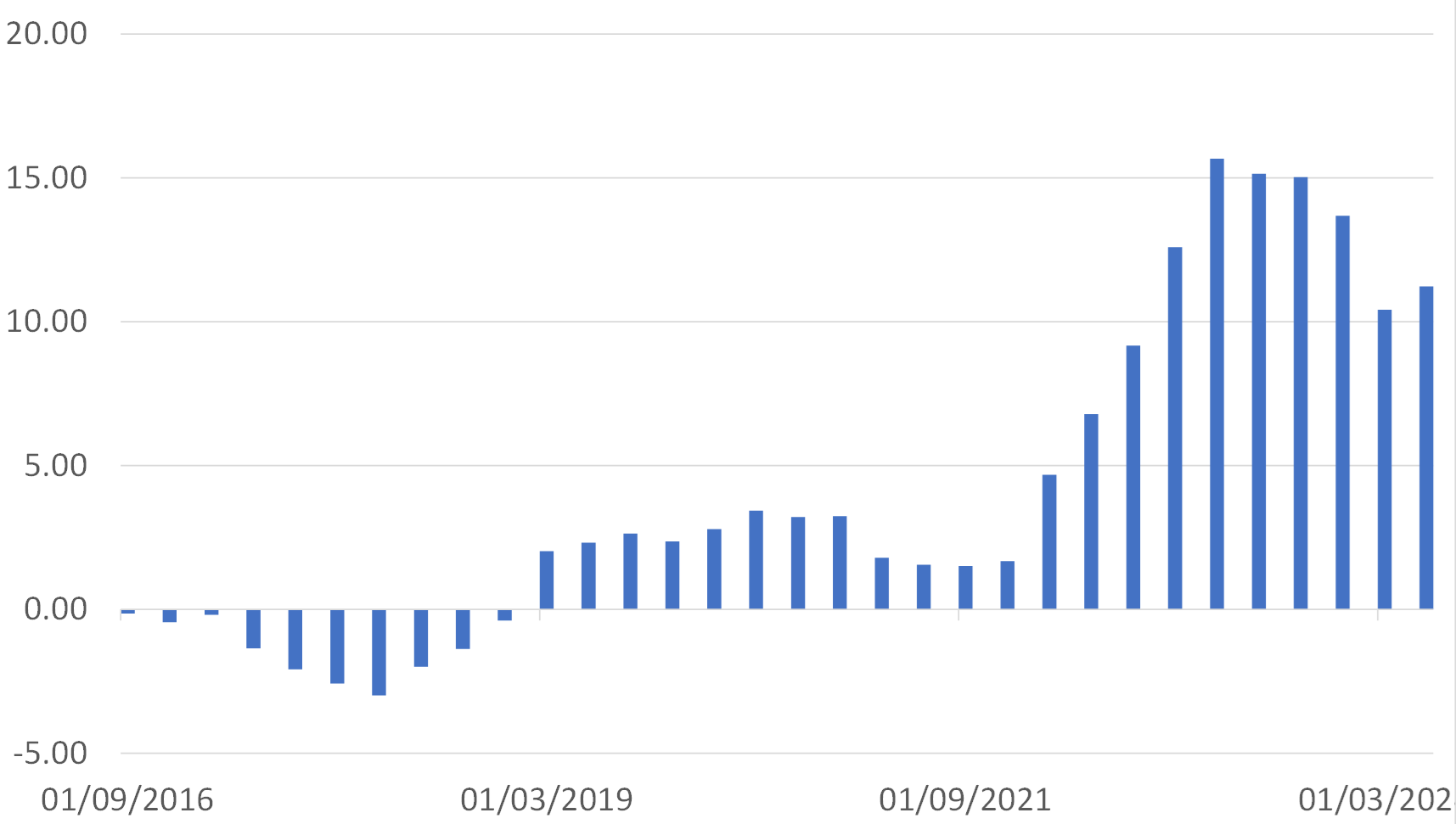

China: Household Financial Balance

RMB trillion over 12 months

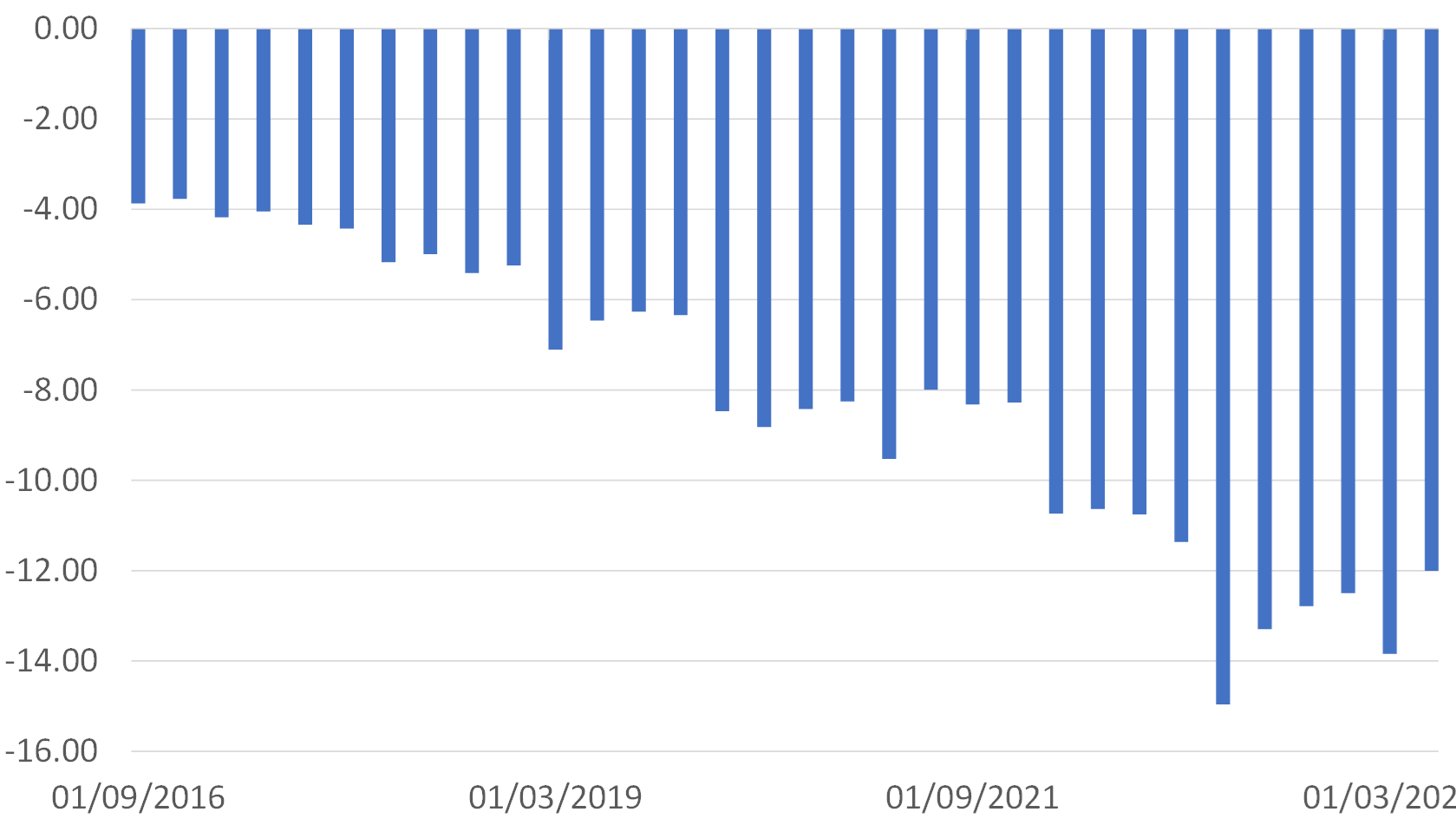

China: Corporate Sector Financial Balance

RMB trillion over 4 quarters

Between the GFC and the Pandemic, China was widely assumed to have been the locomotive for global growth. This was certainly the case between 2008 and 2016, but now China looks set to be a brake on global growth as it deals with the aftermath of the intense credit booms that it experienced from the mid-2000s onwards. There will be no quick fix and unfortunate geopolitical events could serve to amplify the effects of the slowdown as competitors sense weakness and domestic policymakers look to distract the domestic population. China’s problems will affect the rest of the World – albeit asymmetrically across countries – and therefore force a revision of many people’s long-held expectations for the future.

The primary result of this anticipated structural change in household expectations will be to encourage people to save more and dissave less. In all probability, this will lead to weaker consumption trends and perhaps less CAPEX by companies – private sector spending growth will stall. Ordinarily, we would expect this to represent good news for interest rates and yields. As such, the recent rally in the NZD short end may be a portend for others.

New Zealand is interesting in that it is one of the countries that seems set on a fiscal tightening over the medium term. It is likely that the private sector will be seeking to save more and the government to borrow less, with the result that the yield curve should indeed shift downwards by 100 bp or more, albeit at the expense of the NZD’s external value. Being the first to enter the cycle could weigh heavily on the currency, which we expect to decline by more than ten percent over the next year vis-à-vis the later-in-the-cycle USD.

Whether other countries join this “train” will depend on just how their governments respond to the slowdown that is engulfing most of the World outside the US at present. It is quite conceivable that some governments – particularly within the EZ - will simply look to expend their deficits to counter the private sector slowdown. This may support economic activity (spending) in the immediate near term, but at the cost of an ever-larger government role in the economy, something which will likely do little to support long term income growth. There may be another attempt to kick the can down the road, although we suspect that in the EZ this will only work if the ECB “helps out” by returning to QE relatively quickly given the existing size of the EZ deficits.

The US economy is continuing to expend at a reasonable clip, primarily because its fiscal stance remains accommodative and because - in the shadows – it is continuing to experience what we believe to be an intense credit boom in its private sector. Admittedly, this Non-Bank Financial Institution-originated Credit Boom may have stalled over the last few weeks as the Treasury has issued a significant amount of liquidity-sapping debt (hence the softer markets tht we have witnessed of late), but we expect it to restart next month and this, together with a widely-expected pre-election fiscal boost, should support US growth, albeit at the expense of a wider budget deficit and reduced private sector savings.

The US will therefore be going in the opposite direction to everyone else and ultimately this will likely place upward pressure on yields (more precisely, we expect yields to rise when the Fed’s reservoir of liquidity-boosting Reverse Repos are exhausted and the Tresury’s own cash balances are run down – probably in late Q4). It is also quite likely that any pre-election boost to the economy will prove inflationary – by our estimates the US continues to possess a positive output gap and therefore any acceleration in expenditure growth in the run up to the election will likely rekindle core inflation. This too could weigh on the bond markets.

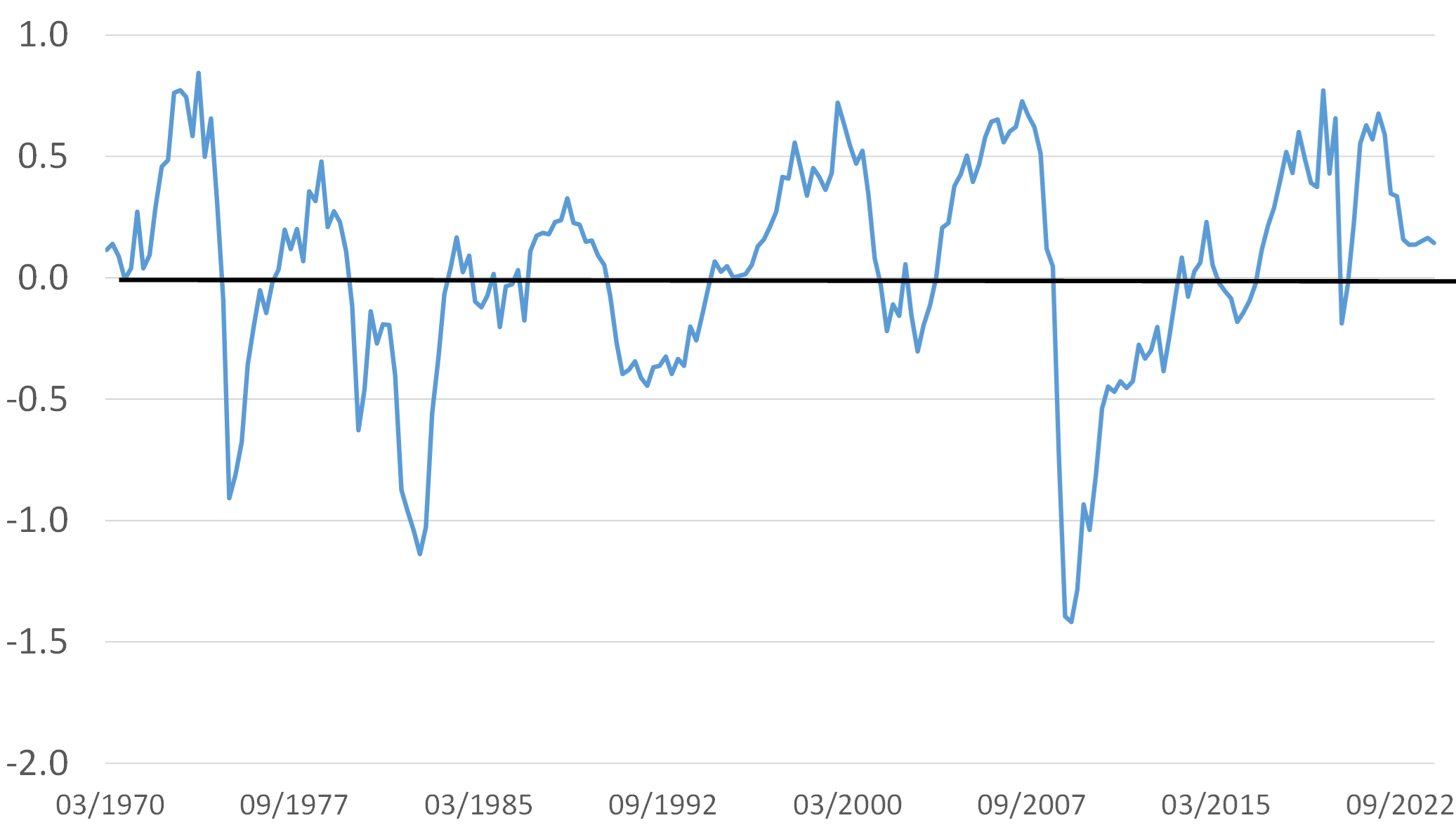

USA: Demand Pressure Index

1970 - 2024Q2

Looking further ahead, we doubt that the US credit boom – or the government’s own finances will be able to “survive” a sustained period of higher yields. Our sense is that even a relatively brief period of yields in the high 5% range, coupled with a probable slowdown in liquidity growth caused by an exhaustion of the RRP reservoir, will be sufficient to compromise the credit boom. The political stage may also have been set by then for a de facto fiscal tightening as the Trump 1 tax cuts are not continued. The US could therefore stumble mid next year and in so doing join the “train” towards higher private saving and lower public sector dis-saving. We may be bearish for UST and bullish the USD in late 2024 but by mid-2025 the US too may be looking for lower yields and the dollar will by then be joining the “race to the bottom”. At this point, currency volatility will likely be driven by news flow and relative policy settings “that week”.

Disclaimer: These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed by Nikko Asset Management New Zealand Limited (Company No. 606057, FSP No. FSP22562), the investment manager of the Nikko AM NZ Investment Scheme, the Nikko AM NZ Wholesale Investment Scheme and the Nikko AM KiwiSaver Scheme. This material has been prepared without taking into account a potential investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs and is not intended to constitute financial advice and must not be relied on as such. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance. While we believe the information contained in this presentation is correct at the date of presentation, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given, and no responsibility is accepted for errors or omissions including where provided by a third party. This is not intended to be an offer for full details on the fund, please refer to our Product Disclosure Statement on nikkoam.co.nz.