2024: a recap

With their central banks bringing interest rates down from previously restrictive settings, 2024 has been the year when most of the world’s economic players have finally begun to experience an easing of monetary policy. In each instance, these reflected confidence that inflation, or perhaps more accurately inflation expectations, had reached a desired level, or were at least on a path towards it.

In many cases these moves were expected, ultimately answering a question of when not if. However, the unknown and unsynchronized timing of them served to create a sense of uncertainty through the first half of the year. The central banks of Canada, the UK and Europe all moved earlier, but with the broader US economy holding up much better than had been feared, the Federal Reserve’s Chair Powell didn’t announce the first cuts there until September. Meanwhile, the Reserve Bank of Australia has not cut rates at all, and the Bank of Japan has moved the other way, finally hiking rates after years of ultra-low monetary policy settings.

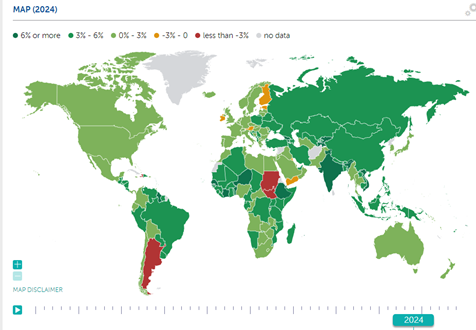

It’s not just the US economy that has fared better than feared. This year, economic growth has held up reasonably well through most parts of the world, with many countries and regions growing at or around long-term averages of 3% in real terms (see map below). Importantly, this growth was better than expected 12 months ago, when there was still concern that key economies would suffer a recession or slowdown of some sort as a result of the restrictive interest rate settings.

Global Real GDP Growth - World Map 2024

Source: International Monetary Fund, October 2024

The combination of reasonable growth and falling interest rates has led to another good year for global equity investors as the S&P500, Nikkei 225, FTSE100 and Eurostoxx 600 all hit new all-time highs this year. With its relatively large exposure to technology-driven sectors, the US market has continued to lead the way. However, compared to 2023, this year has also seen a broadening out of returns with the likes of Japan, Hong Kong, China and Emerging Markets delivering double digit returns.

But alongside this growth, volatility remained a market-defining trend for the year, with bond and equity markets hit by occasional bouts of quickly-shifting sentiment. Driven by changing expectations of when central banks would begin cutting rates, bond market volatility remained at levels not seen since the GFC. Having enjoyed stellar returns at the end of 2023, when lower interest rate settings were priced in, year-to-date returns are more muted, but positive nonetheless (Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index hedged to NZD +2.5% CYTD).

Closer to home, returns in Australasian equities and NZ Fixed Income have also been more muted. The NZX50 Index is up 8.1% CYTD, while the ASX200 Index is up nearly 10%. NZ Fixed Income has outperformed global bond marks with CYTD returns of around 4.5%.

Global outlook for 2025

Turning our attention to the outlook for the global economy for the year ahead, it’s worth mapping out expectations for economic growth, inflation and interest rate settings. Between 2020-2024, from lockdowns through to monetary and fiscal support packages, we’ve had very few periods when at least two of these factors were not either changing or expected to be changing quickly. From here though, it is possible that we are entering into a period where we will return to ‘normal’ levels across all three. For the first time in what seems like a long time, this would see:

- interest rate settings near to neutral, or at least not being drastically adjusted higher or lower as we saw through 2022-2024;

- inflation within or close to the 1-3% band targeted by central bankers; and

- global economic growth (in real terms) around 3%.

In terms of changes still to come in the next calendar year, interest rate settings by central banks will continue to be watched closely. The key factor will be to what extent - and how quickly - lower interest rate settings flow through to the broader economy. Now that most of the major central banks have begun easing, the focus will also turn to how low interest rates will go from here. The ‘new neutral’ level is expected to be higher than the near-zero interest rate policy settings of the post-GFC decade, but exactly where this level is will remain a point of conjecture.

The key risk to the outlook for eased monetary policy settings is another bout of inflation returning. This would put central bankers in a difficult situation. Inflation in goods, food and energy has returned to more normal levels after the wild ride witnessed over the last five years. However, it is in the services sector where prices have continued to rise at a slightly high rate. The services sector is very broad, covering pretty much everything not included in raw materials (primary sector) or manufacturing (secondary sector) – think everything from surgery, to dining out, to rock concerts. In many advanced economies it is also the largest sector, so if inflation there remains above target, it will cause a headache for central banks.

With over 50% of the world’s population having been to the polling booths in 2024, this year had been dubbed the election year. This created periods of uncertainty and volatility and resulted in some surprise outcomes in Japan and Europe, as well as the very clear-cut Republican sweep in the US. The focus for 2025 and beyond will now shift to the new policies that political parties in power are able to roll out, and to what extent they might represent a change to the status quo.

US President-elect Trump was never shy of using tariffs during his first term in office and has talked extensively pre-election about returning to the theme. The distinct possibility of increased, or at least different, tariffs is another inflationary risk.

Tariffs are never a one-way street, and they are very rarely simple in what is a continually evolving global trade framework. An increase to one entity’s cost of doing business could be beneficial or adverse to another’s in a different part of the world; and they can also act as a consumption tax on the end user through higher prices.

Nevertheless, the global outlook for economic growth has definitely improved. For much of the last two years, within the high-interest-rate environment deemed necessary to curb inflation, nations have lived with the threat of economic contraction, whether via a sharp recession (hard landing) or more muted slowdown (soft landing). With most regions having passed the peak in interest rates, there is now the genuine possibility for some of an economic ‘no-landing’, whereby inflation is brought back to target levels without economies first going through the pain of a recession.

While the last few years have been a volatile time for businesses in many industries, overall listed companies have done a good job growing their earnings at a solid rate. Earnings expectations still appear achievable, with the impact of lower borrowing costs expected to flow through to businesses and consumers over the coming year.

Valuations around the world are mixed, and in aggregate, slightly expensive. In the US, valuations are above neutral as high margins and strong earnings growth have led to rich multiples being paid for that growth. Meanwhile, other areas such as Emerging Markets, Europe, UK and Asia are trading below long-term averages. But overall, with the lower interest rate settings we’re now seeing in most economies supportive of gradual economic improvement and therefore an extension of the current market cycle, we expect this next year to see solid returns for the key asset classes.