The ongoing weakness in the yen has led to intense debate over whether Japan can cope with further challenges to its global purchasing power. Dollar-yen is, by most measures of purchasing power parity (whereby an equivalent basket of goods worth a dollar in the US costs less than 100 yen in Japan), far off this measure of “fair value”. However, Japanese officials, particularly those from the Bank of Japan (BOJ), have remained circumspect given the persistence of ongoing mild reflationary signals in the domestic economy. Although Ministry of Finance (MOF) officials have warned against “excessive” or disorderly market moves, dollar-yen volatility remains at an unremarkable level despite the US currency having briefly risen to multi-decade highs above 160 yen.

Of course, economies with large external surpluses, like Japan, hold foreign reserves for the purposes of intervening to defend their purchasing power (often measured in months of imports) where necessary. Still, intervention to defend a currency is very different from intervening to maintain export competitiveness, which involves selling the currency. Although a central bank can always print its own currency, foreign reserve holdings are finite. Moreover, the question of whether to sell a portion of foreign reserves is a separate issue from determining whether a weak currency poses an imminent threat to the economy. In Japan’s case, the MOF decides the former, but addressing the latter involves coordination between the MOF and the BOJ, and sometimes other central banks. The question of “how weak is too weak” is an important one, and it is a topic we address in this report.

How much do import prices matter?

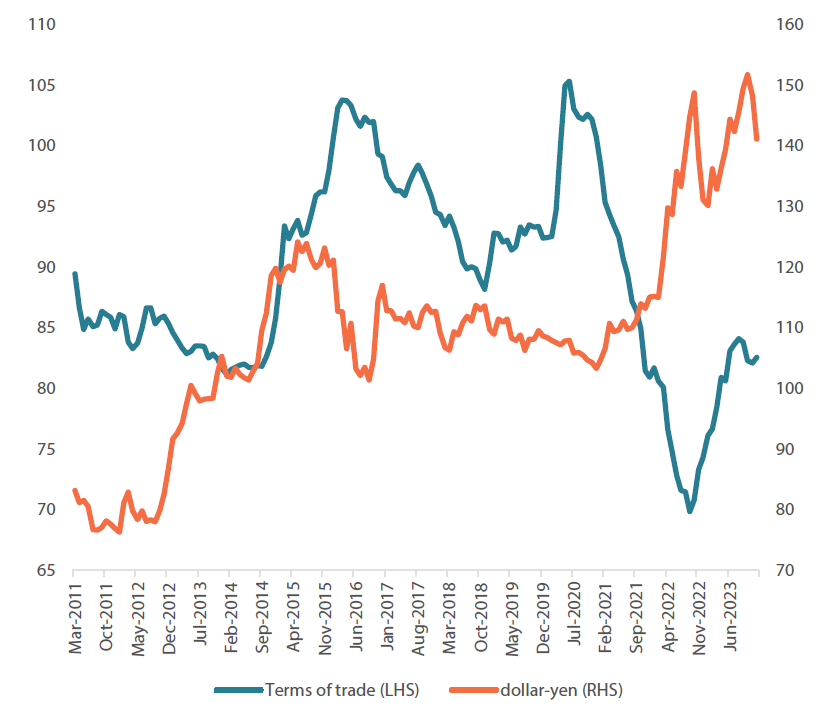

As we have seen, of late, despite the weak yen amplifying dollar-denominated import price inflation over the past few quarters, large corporates have benefited from the boost to nominal non-yen revenues earned overseas. This is one among many reasons corporate profits have recently hit record levels. Conversely, more domestically oriented companies, which tend to be smaller, have only benefited indirectly from increased expenditure by larger client firms, while also seeing pressure from rising import costs. The BOJ favours a measure known as terms of trade (which describes the relationship between export and import prices) as a barometer for external competitiveness. Although this measure currently shows weakness, it is notably stronger than it was in 2022 when imported inflation was much higher (see Chart 1).

Chart 1: Japanese terms of trade and dollar-yen

Source: Nikko AM, Bloomberg

Households, which account for the largest share of Japan’s domestic product, are showing mixed signs. On one hand, they are showing some signs of benefiting from the capacity of large firms and their clients to raise wages. On the other hand, real balances are crucial, and data on household real income has not yet turned positive year-on-year due to inflation. This has kept consumption muted.

To the extent that import prices affect core consumer prices, and given that dollar-yen levels influence import prices, yen weakness does have the potential to impact consumer choice. Therefore, we will examine further the extent of the influence dollar-yen moves have on import prices, and in turn, how much these import prices affect core consumer prices. This analysis will help us understand the conditions under which a weak yen might undermine a recovery in household real income.

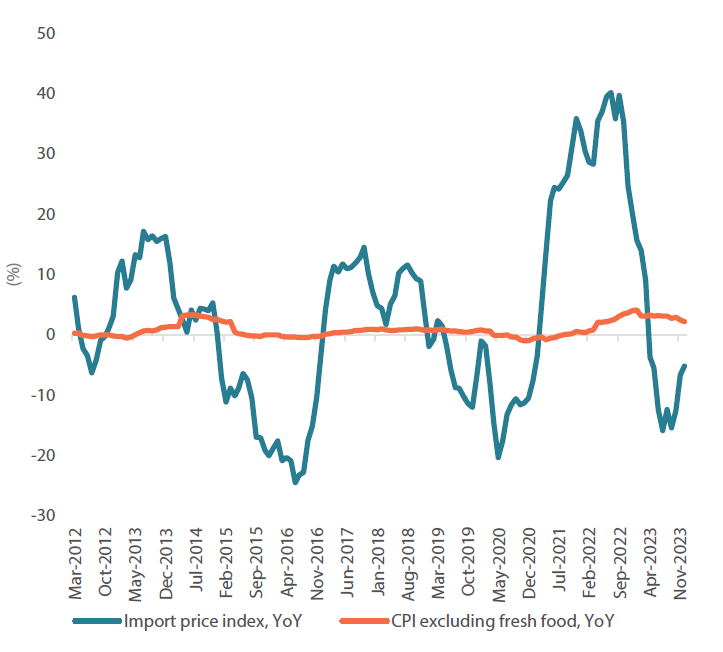

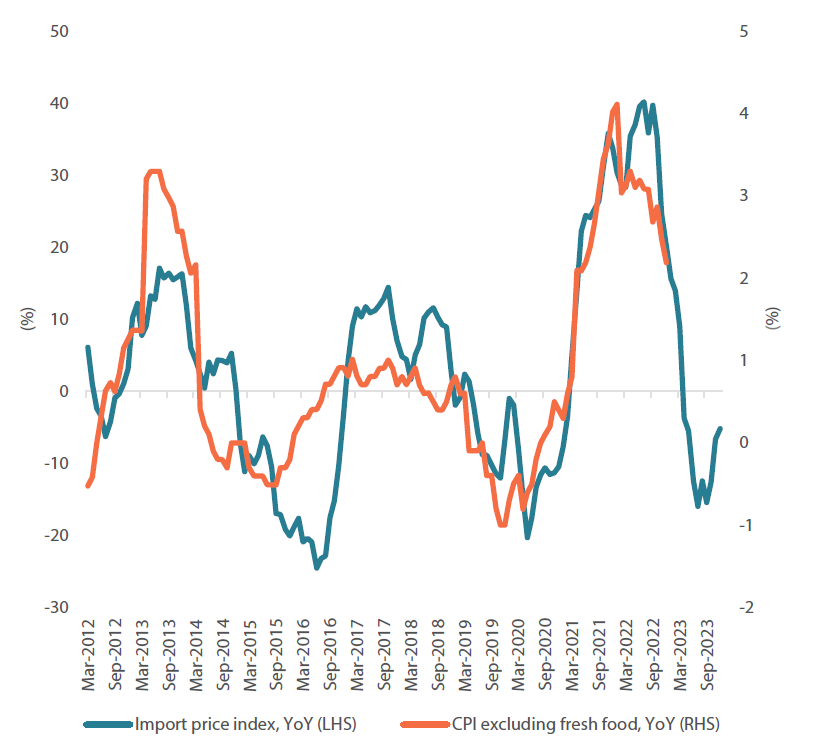

Import prices matter more if we are still in a state of shock

Typically, households enjoy some degree of insulation against swings in import prices. As Chart 2 shows, Japan’s CPI excluding fresh food tends to be much more stable than its import price index. Even with Japan’s increased reliance on imported fossil fuels following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, we estimate that less than 30% of Japan’s import prices have filtered through to core consumer prices over this period, with a 13-month lag (even less without the lag). That said, it is possible that we are living in exceptional times. If we observe the more volatile price moves from March 2020, which marked the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, we discover that the correlation between import prices and core CPI roughly doubles, and is at its strongest with a 13-month lag (see Chart 3). Assuming that we are still navigating the implication of price shocks, it is reasonable to assume that import prices are currently more impactful to households than they typically would be.

Chart 2: Japan import price index (% YoY) and CPI excluding fresh food (% YoY)

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 3: Import prices (% YoY) and CPI (% YoY, with 13-month lag), rescaled

Source: Bloomberg, Nikko AM

How responsible is yen weakness for higher import prices?

Yen levels are not the only factor influencing Japanese purchasing power. As we saw in 2022, a spike in oil prices can potentially have a much stronger influence over terms of trade. Since then, however, the surge in oil prices has abated. Barring a shock development for oil prices, we discover that statistically, dollar-yen tends to be a much more significant driver of import prices than crude oil prices over time; we estimate that all else being equal, since March 2011, a 1% move in dollar-yen has had the potential to move import prices by half a percent. So long as import prices are a factor, dollar-yen also matters, even when oil prices are not inducing shocks.

Why not to panic over a soft yen (for now)

Dollar-yen is indeed hovering at multi-decade highs. Yet it would be premature to blame the yen for undermining Japan’s nascent domestic recovery. One reason for this is that historic nominal wage increases may yet outpace the drag of higher import prices upon real income growth.

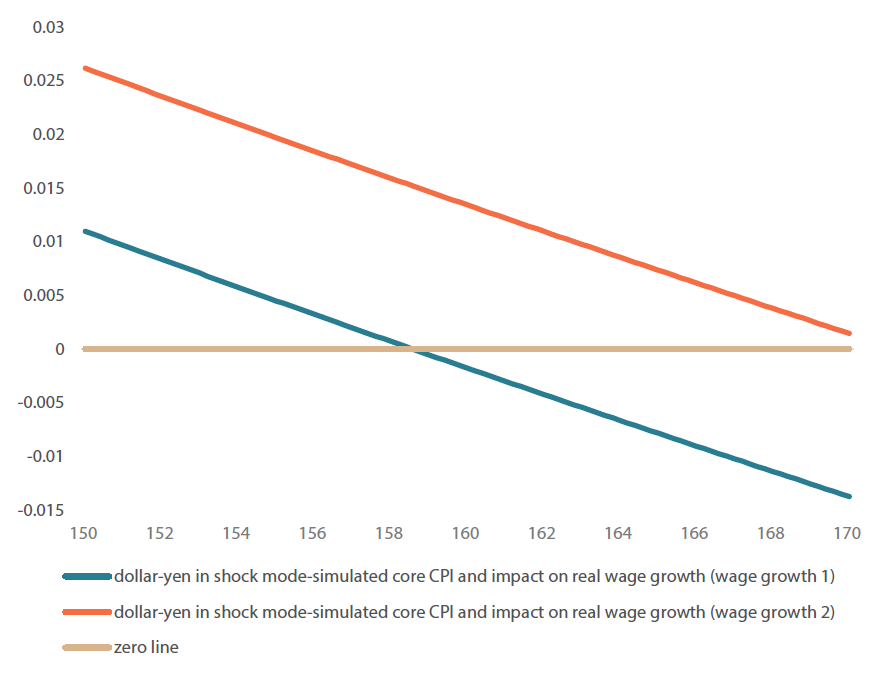

To illustrate this point, we estimate real wage growth under two wage assumptions. One is based on the most recent figure on annual wage increases reported by Japan’s largest trade union organisation, Rengo, from the annual spring negotiations, which stands at 5.24% year-on-year. Recognising that this growth may only have a limited spillover effect on the general economy, in our second assumption we also consider the lowest sector-specific annual gains (from the services sector) as reported by Rengo, which is a growth rate of 3.72%. We then simulate the influence of yen weakness from the end of fiscal year 2023 (during which dollar-yen ended the year at 151.35) upon real wage growth over the current fiscal year, assuming average dollar-yen levels between 150 and 170 over the period.

Our observation shows that even assuming an ongoing “supply shock” environment for imports, it is only when dollar-yen appreciates and continues to do so that it is likely to undermine real wages at the lower nominal growth rate of 3.72%. The average dollar-yen rate would have to be 158 over the entire fiscal year, which assumes that it spends at least half the year above this level (see Chart 4).

Chart 4: How much additional damage could a weak yen do with core CPI at 2.8%?

Source: Nikko AM

Currencies fluctuate, and a weak yen is not as bad as a weakening yen

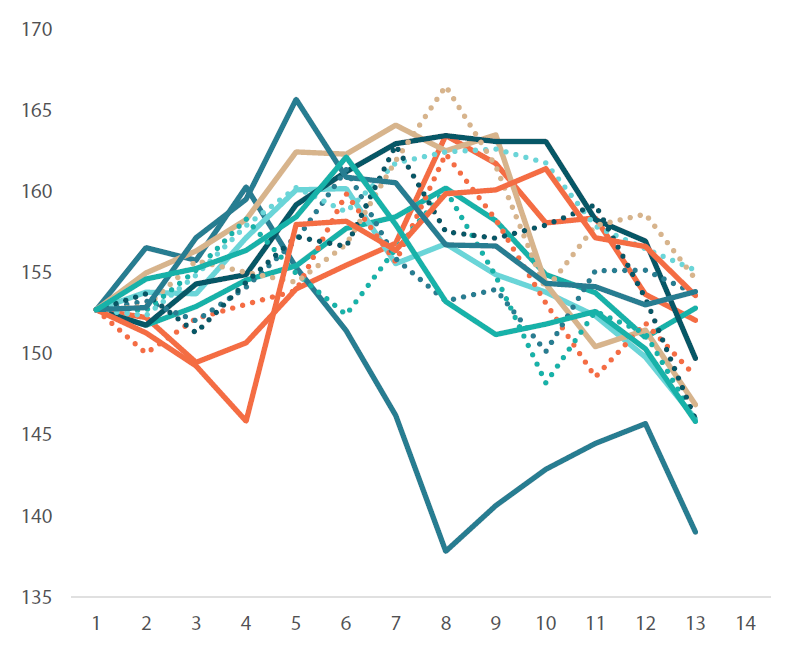

To further emphasise the importance of not panicking over currency fluctuations and instead paying greater attention to longer-term trends, we performed a simulation of dollar-yen 12 months forward (to the end of the current fiscal year through March 2025). This simulation uses volatility patterns observed since March 2011, more recent currency trends, and the tendency of the currency pair to show clusters of higher and lower volatility over time.

By this measure, there is only a small probability of dollar-yen showing a sustained appreciation trend large enough to erode real wage gains over the current fiscal year. Meanwhile, there is a much greater probability of dollar-yen spending some time even at or above 160 without damaging real household income prospects. We illustrate some of these possible paths in Chart 5.

Chart 5: Simulated dollar-yen paths averaging below 155 and touching 160

Source: Nikko AM

Accept the weak yen for now, but be vigilant of a sustained downtrend

In conclusion, we believe that there is no need to panic over current dollar-yen levels, or even temporary increases toward or above 160 as seen recently. However, if there were any market dislocations resulting in a sustained uptrend for the currency pair, this could prompt the BOJ to express greater concern about excessive yen weakness inviting inflation and undermining the “virtuous circle” of reflation and recovery.

Otherwise, we expect the BOJ to remain laser-focused on developments in prices and consequently real household income to determine when it will withdraw further accommodation.